“Traces” Frederieke Jochems, Wanda Michalak, Paul Schäublin 17.04 – 21.08.2021

January 19, 2021 11:40 amGallery WM is delighted to present:

Traces

by the families of:

Frederieke Jochems

Wanda Michalak

Paul Schäublin

curated by Sebastian Rypson

17 April through 21 August 2021

In July and August open on request – for appointment call 06 42 93 43 35 or 020 421 11 13

Anecdotal rediscoveries from our family photo-albums.

From April 17th through August 21nd Gallery WM will showcase anecdotal excerpts from the photo-albums of three people; Wanda Michalak, Paul Schaublin and Frederieke Jochems. Ranging from 1900 to 2000, from black-and-whites to colour, from clichés to the exceptional, originals to reprints. These are rediscovered windows into the lives of three different families; lives led, loves lived and lost lineages. An intimate look at family dynamics from Cape Town to Gibraltar and from Poland to The Netherlands.

Poland in the late 40’s, just after the 2nd World War – “My Parents” (W.Michalak)

Traces

“Traces” showcases rediscovered, anecdotal excerpts from three families’ photo albums; those of Wanda Michalak (Polish), Frederieke Jochems (Dutch) and Paul Schäublin (British-Swiss). All three have written personal texts about their rediscoveries below. Suffice to say, these unearthed selections came about during clean-ups and re-organisations of attics, basements and archives after the passing of loved ones, and during the Covid-mandated isolations that have impacted all of us. What we have selected ranges from the exceptional to the mundane, from black & white to colour, from 1900s to the 2000s. Jochems’ selection focuses on her two aunts; aunt Tabitha and her daughter aunt Bets. In it, we see an amateur conceptualism; mother and daughter taking pictures of each other in the same place, with the same background, spanning three decades. Schäublin has chosen a limited selection of photographs from the 1910’s and ’20’s, immortalising the migration of his grandmother Cleopatra, from Cape Town to Gibraltar and Spain. Proof that labour migration has been around forever and always will be. Michalak’s selection, forming the majority of the exhibition, focuses on her mother – my beautiful grandmother – and the extended family and friends that populated her life before the Second World War, during, and after.

I don’t think it is merely a coincidence that family albums have been uncovered, rediscovered, pored over and re-organised. When life outside – our former social lives – has all but come to a halt, from one moment to the other, it does not seem so strange that our gaze and focus should turn inwards, as just one glance outwards simply reconfirms the literal lockdown of external life as we used to live it. So why do we gaze at those old family photos? What subliminal messages are our forefathers sending us, do you think? Maybe it’s just that looking at lives lived is a way for us to feel alive ourselves. Maybe it has to do with an affirmation, that “yes, lives before me were led, there was drama, there was trauma, but there was also happiness, trips to the capital, birthday parties, holy communions, family portraits … and I am living life, much in the same way …”? Perhaps it is a reaffirmation of one’s own existence, as evidenced by the existence of lives having been led by our families?

Something happens to us when we gaze at our forefathers from former lives and loves. We know, cognitively at least, that these people were/are a prerequisite for our own existence. We look at lives a lifetime ago, and know, that if any small and tiny thing had played out differently, we might not have been born. If any one of our extended family had died in childbirth, had not survived the war, had lived life differently, had fallen in love with someone else, our existence would be in serious question ; our lives an extremely tenuous thing.

Perhaps. Personally, I am fascinated and emotionally invested with these traces of our families’ existence. I see my grandmother, a hundredfold, younger than I am now, living life with abandon, dancing on the edge of a metaphorical volcano. Having fun, flirting, posing, glancing coquettishly into the camera lens. She was born, she was young, she had fun, and lived through hell. She had children, grew into middle age, became a grandmother, and finally passed away. I am, because she was. And what beautiful traces she left.

Sebastian Rypson

Poland in the 30’s

We, the guardians of our Traces – Wanda Michalak

When my grandmother frantically packed her things to flee the approaching Germans in 1939, she took with her a couple of duvet blankets, … and her photo albums. Or so the family story goes.

They were forced to flee a few times more before they were allowed to go home, to the provincial town of Ciechanów, near the border of Eastern Prussia. Each time, the family albums went with them. Accused of being involved in anti-German activity, my mother went into hiding on farms and in villages that surrounded her hometown. She was betrayed however, and my mother ended up in a forced-labour camp, a subcamp of the Stutthoff concentration camp system.

The first guardian of the photo albums was my grandmother. Later on, it became my mother. As a sickly child I was often in bed with one thing or another, and in order to pacify me, my mother would give me the albums to look at. This was probably not a great idea as I would proceed to colour them in with my crayons!

This show is all about my mum.. but also my grandmother. And my father. And all the unknown people who are exhibited here. I don’t know who they are, but they were part of my mother’s life. I can’t ask my mother who they were any more.

I am the guardian of the albums now. And my son. And then his son. Hopefully.

Wanda Michalak

Wanda Michalak (right) with grandmother and mother in the early 70’s

Aunt Tabitha and Auntie Bets – Frederieke Jochems

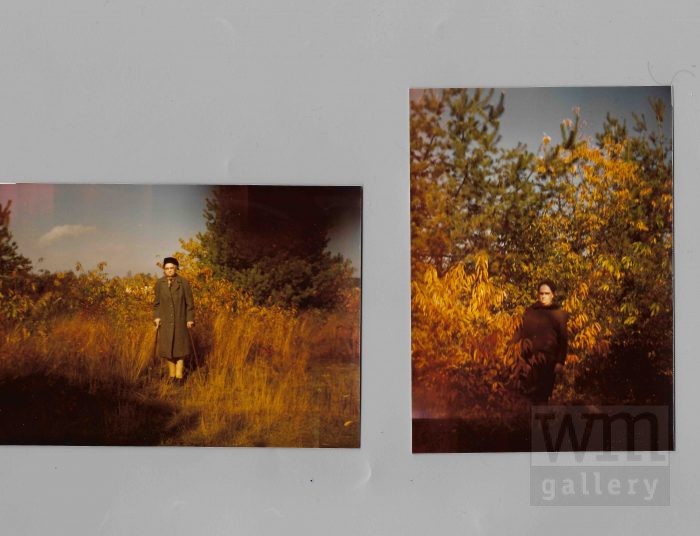

In the legacy of my mother I found my aunts photo albums. Since childhood I knew this aunt Tabitha (wife of my grandfather’s brother) and her daughter Bets. Husband/father Johannes died in 1945, mother and daughter lived together since then as far as I can remember. For my birthday I always received a card from them with 5 guilders folded in it. When travelling by bike I sometimes visited them in Ermelo. Aunt Tabitha died in 1988, her daughter Bets soon after.

One of their photo albums struck me more than the others. It recalls their holiday trips during the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, when they travelled to Luxembourg, Valkenburg or Maastricht. Besides visiting castles and cities they posed in a flower garden, on a heath, in front of an autumn forest or in and around their home. They always took a picture of one another on the same spot with exactly the same background. For this exhibition I want to draw attention to these photos in particular because I consider them interesting in a photographic sense: the consistency and planned attitude ( familiar to myself ) by which they executed their photographic actions. In spite of – or maybe thanks to – their amateurism the pictures are sometimes beautiful and aesthetic. If you look carefully you will see that the series tells their story, revealing subconsciously their mother/daughter relationship. In current times, in which people continuously take pictures of themselves, compulsively smiling, I regard their honest unadorned grumpiness as a relief.

Frederieke Jochems

Tabitha & Bets young

From Cape Town to Gibraltar – Migration in the Colonial Times – Paul Schäublin

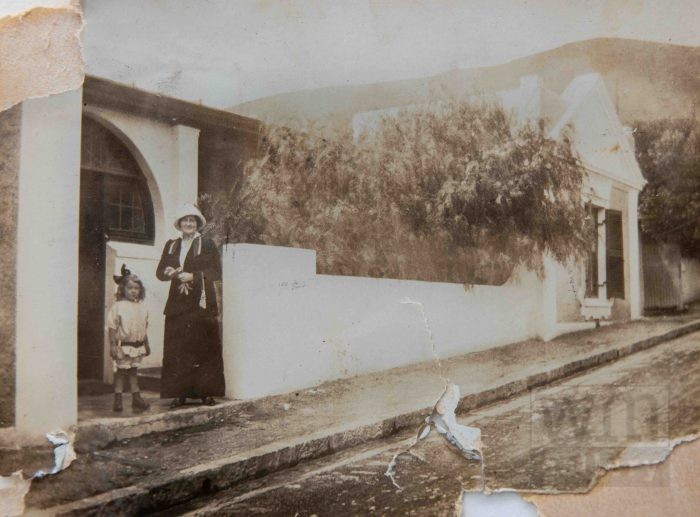

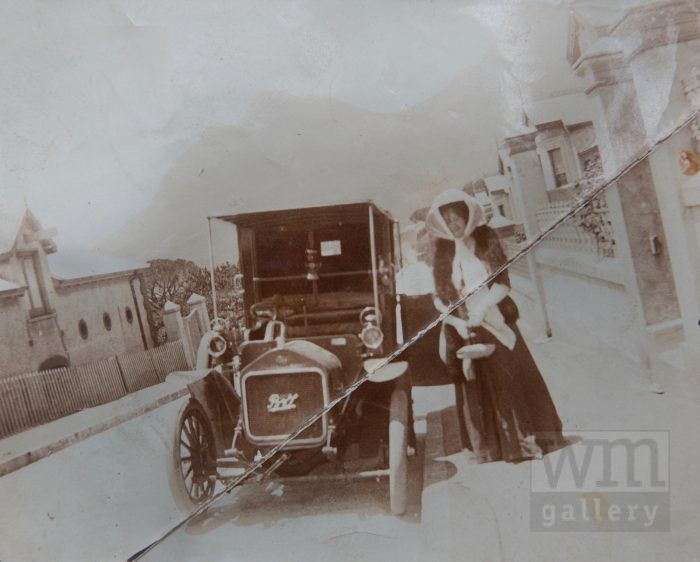

Hundred years ago, in 1921, the Oakley family – my maternal grandparents and their 3 children – relocated from Cape Town (South Africa) to Gibraltar. My grandfather Eddy Oakley was working at the time for the Eastern Telegraph Company (a British telegraph communication company) and after some 10 years spent in South Africa he got a new assignment in Gibraltar. The family comprised Eddy (42), his wife Cleopatra (34 – my grandmother) and their 3 children Phyllis (10 – my future mother), Frank (8) and Vera (4). The Oakley’s travelled by ship from Cape Town to Gibraltar via Southampton (England).

The vessel for the Cape Town – Southampton leg was the “Edinburgh Castle” from the Union Castle Line. It arrived in Southampton 6 June 1921 after a two weeks cruise. The travel must have been a pleasant time. I recall my mother mentioning there was a big party on board when they crossed the equator, this was the so-called “Crossing the line ceremony”. The ship on the Southampton – Gibraltar two days leg was the “Narkunda” from the P&O line.

Thanks to the assistance of my friend Pete Purnell and by consulting the National Archives of the UK, we discovered detailed documentation (mainly passenger list information) regarding the travel my family made. I was totally flabbergasted when I saw these hundred year old handwritten lists. It was for me a huge jump in the past, unearthing traces from forgotten times, almost like exploring the Titanic. It was also an opportunity to revisit the few remaining family photos of that time I still possess and contemplate them from a new perspective.

The Oakley family lived in and around Gibraltar until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil war in 1936. Grandfather Eddy sadly passed away in December 1933. My parents met in Gibraltar and got married there in January 1935. My father Emilio was a Swiss migrant who left his country in 1928, seeking for a better life in South Europe, first in Spain and later in the British colony.

Paul Schaublin

Cape Town ca 1915 – Cleopatra (Granny Cleo) and daughter Phyllis (my future mother)

Opening speech April 17th, 2021 by curator Sebastian Rypson

Media

Walter van Teeffelen about Frederieke Jochems: here

*********************************************************

Traces

door de families van:

Frederieke Jochems

Wanda Michalak

Paul Schäublin

samengesteld door Sebastian Rypson

bij

Gallery WM

17 april t/m 21 augustus 2021

In July en August open op verzoek – voor afspraak bell 06 42 93 43 35 of 020 421 11 13

Anekdotische herontdekkingen uit onze familiefotoalbums.

Van 17 april tot 21 augustus toont Gallery WM anekdotische fragmenten uit de fotoalbums van drie mensen; Wanda Michalak, Paul Schaublin en Frederieke Jochems. Beginnend rond 1900 tot 2000, van zwart-wit tot kleur, van clichématig tot uitzonderlijk, van originelen tot herdrukken. Dit zijn herontdekte vensters naar de levens van drie verschillende families; geleidde levens, geleefde liefdes en verloren familieleden. Een intieme kijk op de gezinsdynamiek van Kaapstad tot Gibraltar, van Polen tot Nederland.

Traces

“Traces” toont herontdekte anekdotische fragmenten uit de fotoalbums van drie families; die van Wanda Michalak (Pools), Frederieke Jochems (Nederlands) en Paul Schäublin (Brits-Zwitsers). Alle drie hebben ze hieronder persoonlijke teksten geschreven over deze herontdekkingen. Het volstaat te zeggen dat deze herontdekte selecties tot stand zijn gekomen tijdens het opruimen en reorganiseren van zolders, kelders en archieven na het overlijden van dierbaren, en tijdens de door Covid opgelegde isolaties die ons allemaal heeft getroffen. Wat we hebben geselecteerd, varieert van het uitzonderlijke tot het alledaagse, van zwart-wit tot kleur, van de jaren 1900 tot de jaren 2000. Jochems’ selectie concentreert zich op haar twee tantes; tante Tabitha en haar dochter; tante Bets. Daarin zien we een charmant fotografisch amateurisme, gekoppeld aan een opvallend conceptualisme; moeder en dochter maken foto’s van elkaar op dezelfde plek, met dezelfde achtergrond, verspreid over drie decennia. Schäublin heeft gekozen voor een beperkte selectie van foto’s uit de jaren 1910 en ’20, waarin de migratie van zijn grootmoeder Cleopatra van Kaapstad via Southhampton naar Gibraltar en Spanje is vereeuwigd. Een bewijs dat arbeidsmigratie altijd al heeft bestaan en dat ook altijd zal doen. Michalaks selectie, die het grootste deel van de tentoonstelling vormt, concentreert zich op haar moeder – mijn prachtige grootmoeder – en de uitgebreide familie en vrienden die haar leven in Polen bevolkten vóór de Tweede Wereldoorlog, tijdens en daarna.

Het kan geen toeval zijn dat familiealbums worden blootgelegd, herontdekt, aandachtig bekeken en opnieuw georganiseerd. Als het leven buiten – wat ooit ons sociale leven was – van het ene op het andere moment bijna tot stilstand is gekomen, is het niet zo vreemd dat onze blik en focus naar binnen wordt gekeerd. Slechts één blik naar buiten bevestigt eenvoudigweg de letterlijke lockdown van het externe leven zoals we het vroeger leefden. Maar waarom staren we naar die oude familiefoto’s? Welke subliminale verhalen vertellen onze voorouders ons? Misschien is het gewoon dat het kijken naar geleefde levens een manier is om onszelf levend te voelen. Misschien is het een bevestiging dat “ja, levens vóór mij werden geleid, er was drama, er was trauma, er was ook geluk, uitstapjes naar de hoofdstad, verjaardagsfeestjes, heilige communies, familieportretten .. en ook ik leef het leven, veelal op dezelfde manier .. ”? Misschien is het een herbevestiging van het eigen bestaan, zoals blijkt uit het bestaan van levens geleid door onze grootvaders en grootmoeders?

Er gebeurt iets met ons als we naar onze voorouders kijken uit vorige levens en liefdes. We weten, althans cognitief, dat deze mensen een voorwaarde waren / zijn voor ons eigen bestaan. We kijken naar levens van een leven geleden en weten dat als één pietluttig iets zich anders had afgespeeld, we misschien niet geboren waren. Als iemand uit onze uitgebreide familie tijdens de bevalling was overleden, de oorlog niet had overleefd, een ander leven had geleid, verliefd was geworden op iemand anders, zou ons bestaan erg twijfelachtig geweest zijn; ons leven is een buitengewoon fragiel iets.

Misschien. Persoonlijk ben ik gefascineerd en emotioneel geraakt door deze sporen van het bestaan van onze families. Ik zie mijn grootmoeder, honderdvoudig, jonger dan ik nu, levend met overgave, dansend op de rand van een metaforische vulkaan. Ze heeft plezier, ze flirt, ze poseert, koket in de cameralens kijkend. Ze werd geboren, ze was jong, ze had plezier en moest toen door de hel. Ze kreeg kinderen, groeide op tot middelbare leeftijd, werd grootmoeder en uiteindelijk, stierf ze. Ik ben, omdat ze was. En wat een prachtige sporen heeft ze ons nagelaten.

Sebastian Rypson

Poland – moeder Michalak

Wij, de hoeders van onze sporen – Wanda Michalak

Toen mijn grootmoeder in 1939 in allerijl haar spullen inpakte om de naderende Duitsers te ontvluchten, nam ze een paar dekbeddekens mee, … en haar fotoalbums. Althans, zo gaat het familieverhaal. Ze moesten nog een paar keer vluchten voordat ze naar huis konden terugkeren, naar de provinciestad Ciechanów, vlakbij de grens met Oost-Pruisen. Elke keer gingen de familiealbums mee. Mijn moeder werd ervan beschuldigd betrokken te zijn bij anti-Duitse activiteiten en dook onder op boerderijen en in dorpen rondom haar geboorteplaats. Ze werd echter verraden en mijn moeder belandde in een dwangarbeiderskamp, een subkamp van het concentratiekamp-systeem Stutthoff.

De eerste hoeder van de fotoalbums was dus mijn grootmoeder. Later werd het mijn moeder. Als ziekelijk kind lag ik vaak met het één of ander in bed, en om me te sussen, gaf mijn moeder me de albums om naar te kijken. Dit was waarschijnlijk geen geweldig idee, aangezien ik ze zou gaan inkleuren met mijn kleurpotloden!

Deze tentoonstelling gaat helemaal over mijn moeder .. maar ook over mijn grootmoeder. En mijn vader. En alle onbekende mensen die hier tentoongesteld worden. Ik weet niet wie ze zijn, maar ze maakten deel uit van het leven van mijn moeder. Ik kan mijn moeder niet meer vragen wie ze waren.

Ik ben nu de hoeder van de albums. En mijn zoon. En dan zijn zoon. Hopelijk.

Wanda Michalak

******

Tante Tabitha en tante Bets – Frederieke Jochems

In de nalatenschap van mijn moeder vond ik fotoalbums van mijn tantes. Van kinds af aan kende ik deze tante Thabita – vrouw van de broer van mijn opa – en haar dochter Bets. Echtgenoot/vader Johannes overleed in 1945, moeder en dochter bleven achter en woonden sinds ik mij kan heugen samen. Voor mijn verjaardagen werd mij altijd een kaartje met een briefje van vijf gulden gestuurd. Op fietstocht door Nederland ging ik wel eens op bezoek bij hen in Ermelo. Tante Thabita overleed in 1988, haar dochter Bets niet lang daarna.

Een van hun fotoalbums trof mij in het bijzonder. Het getuigt van hun gezamenlijke vakantietrips in de jaren ’60, ’70 en ’80 wanneer zij op stap gaan naar Luxemburg, Valkenburg of Maastricht. Naast steden of kastelen die ze bezoeken, staan ze te poseren in een bloementuin, een heideveld, herfstbos of in en rondom hun huis. Steeds maken ze een foto van elkaar op dezelfde plek met exact dezelfde achtergrond. Voor deze expositie licht ik deze foto’s eruit omdat ik ze fotografisch interessant vind: Hun consequentheid en planmatigheid (die ik herken) die ze hadden bij het fotograferen. Ondanks of dankzij hun amateurisme zitten er prachtige esthetische plaatjes bij. De serie vertelt voor de goede verstaander hun verhaal, en geeft onbewust een inkijk in hun complexe moeder-dochter relatie. In de huidige tijd, waarin mensen continu zichzelf dwangmatig lachend fotograferen, vind ik het onopgesmukte eerlijke chagrijn van mijn tantes een verademing.

Frederieke Jochems

Tabitha en Bets, Herfst / Fall

******

Van Kaapstad naar Gibraltar – Migratie in de koloniale tijd – Paul Schäublin

Honderd jaar geleden, in 1921, verhuisde de familie Oakley – mijn grootouders van moederskant en hun drie kinderen – van Kaapstad (Zuid-Afrika) naar Gibraltar. Mijn grootvader Eddy Oakley werkte destijds voor de Eastern Telegraph Company (een Brits telegraafcommunicatiebedrijf) en kreeg na zo’n 10 jaar in Zuid-Afrika een nieuwe opdracht in Gibraltar. Het gezin bestond uit Eddy (42), zijn vrouw Cleopatra (34 – mijn grootmoeder) en hun 3 kinderen Phyllis (10 – mijn toekomstige moeder), Frank (8) en Vera (4). De Oakley’s reisden per schip van Kaapstad naar Gibraltar via Southampton (Engeland).

Het schip voor de etappe Kaapstad – Southampton was de “Edinburgh Castle” van de Union Castle Line. Het kwam op 6 juni 1921 aan in Southampton na een cruise van twee weken. De reis moet een plezierige tijd zijn geweest. Ik herinner me dat mijn moeder zei dat er een groot feest aan boord was toen ze de evenaar overstaken, dit was de zogenaamde “Crossing the line-ceremonie”. Het schip op de twee dagen durende reis tussen Southampton – Gibraltar was de “Narkunda” van de P & O-lijn.

Dankzij de hulp van goede vriend Pete Purnell en door de “National Archives of the UK” te raadplegen, vonden we gedetailleerde documentatie (voornamelijk passagierslijstinformatie) over de reizen die mijn gezin maakte. Ik was stomverbaasd toen ik deze honderd jaar oude lijsten ontdekte. Het was voor mij een enorme sprong in het verleden, waarbij ik sporen uit vergeten tijden ontdekte, bijna alsof ik de Titanic verkende. Het was ook een gelegenheid om de weinige overgebleven familiefoto’s uit die tijd die ik nog bezit opnieuw te bekijken en ze vanuit een ander perspectief te beschouwen.

De familie Oakley woonde in en rond Gibraltar tot het uitbreken van de Spaanse burgeroorlog in 1936. Grootvader Eddy overleed helaas in december 1933. Mijn ouders ontmoetten elkaar in Gibraltar en trouwden daar in januari 1935. Mijn vader Emilio was een Zwitserse migrant die zijn land verliet in 1928, op zoek naar een beter leven in Zuid-Europa, eerst in Spanje en later in de Britse kolonie.

Paul Schäublin

Cape Town ca 1911 “She doesn’t look so “miserable” as her letters seem to convey eh? This is how mrs Oakley comes home from town! The parcels contain little things for the “newcomer””(note on the back of the photo)

Opening speech 17 april 2021 door curator Sebastian Rypson

Media

Walter van Teeffelen over Frederieke Jochems: hier

Tags: Frederieke Jochems, Paul Schäublin, Wanda Michalak