Sea map – Personal objects and stories

February 8, 2023 6:12 pm

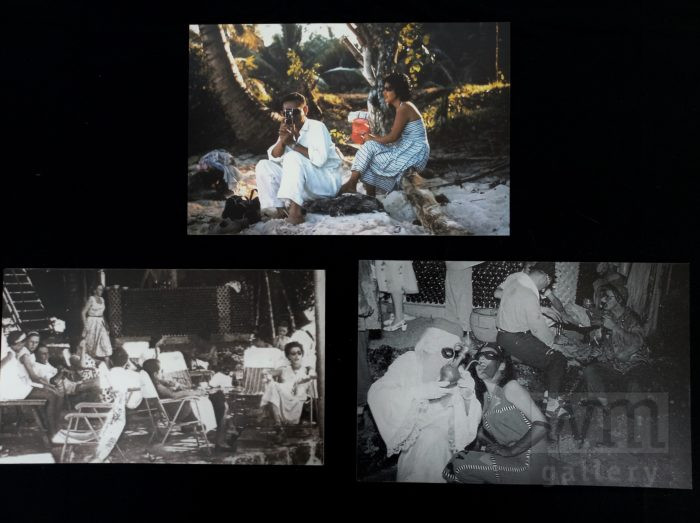

3 photos of De Flessenbar (The Bottle Bar). Photo of Ingrid Hooper’s parents.

Year: 1950s

Biak, Dutch New Guinea

Photos by Ingrid Hooper

I was born on Biak, in 1954. My father worked for KLM on Biak. There was a lot of drinking by the KLM staff. In the early 1950s there was not much to do on Biak, so you had to organize it all on your own. The partying was done at home, but it was also done at KLM. Many staff parties were thrown in what was then called the KLM hotel, but afterwards, in the early hours, people went to the beach behind the KLM hotel and apparently they continued to party there. There was so much partying there that they built a bar from all those empty beer bottles. The Bottle Bar. And a dance floor because there was also intense dancing.

This is a picture of my parents. It’s so beautiful it’s almost too painful to look at. It’s my memory, it’s nostalgia. My father always said – My Biak years are the best years of my life. And then the construction of De Flessenbar was mentioned in the same breath. When we returned to Biak in 2015 after 26 years, we went looking for De Flessenbar. We walked all the way to the Beaver slope next to the KLM Hotel. But there was nothing to be found and disappointed we went back to our hotel. In 2018 we were back on Biak together with our son and started looking again. With hardly more information than in 2015, we took the same path down. We now went not to the left but to the right. And yes! There we clearly saw the fragile remains of De Flessenbar. What happened in and around me is hard to describe. It was a fusion of images, sounds and smells from 60 years ago and those of the here and now. I heard the music from that time and saw my parents dancing on the dance floor. I even heard their laughter in my imagination. I was thrilled to see them like this and emotional at the same time because it’s all over. We danced on the dance floor and shouted: “Thank you Mum and Dad, Grandpa and Grandma!” I feel grateful that I am a child of my parents and that they brought me into the world in this paradise place on earth.

Ancestor figurine

Year: unknown

Geelvink Bay, Dutch New Guinea

Loan from Marieke Marisan

I was born on July 31, 1954 in Waupnor on the island of Biak in Geelvink Bay. My Papuan parents were Paulus Marisan and Doortje Suruan. My father died of tuberculosis three months before I was born, which was prevalent in all of West Papua at the time. My mother died of a hemorrhage shortly after giving birth. Ali Brinkman, a nurse, had found me near the hospital where a relative had taken me. She took me to the hospital on Biak where I grew up as an orphan. She took care of me together with head nurse Rens van der Zee. In 2010 when Ali Brinkman passed away, her niece Mieke Wakker contacted me and I received this statue. So it is an inheritance from Ali Brinkman, who named me Mieke after her cousin in the Netherlands. I was raised by Dutch nursing as well as Papuan nursing and care. In 1955, my later adoptive father, Willem Janssen, started working as a government doctor in the hospital of the former Government of Dutch New Guinea, in Biak. In March 1957 he arranged all the paperwork necessary for adoption. An uncle of mine, Gerard Marisan, teacher at the village school in Mnurwar had given permission for the adoption.

In 1961 we left for the Netherlands. In Berkel en Rodenrijs I was the only dark child in the village. My father always talked to me about my country, and about my people. He also thought it was important that I should bear my own family name, Marisan, which I am also very proud of. I waited too long before I went back to Biak for the first time, that was in 2007. Then I saw those people for the first time and I thought “they also have those hamster cheeks – no question; I’m a Marisan”. This is how I got to know more people from my family. I didn’t speak my own language, still don’t. But it wasn’t a problem for them, they also spoke Dutch. I also visited the house where I was born, which was very emotional. I also met my cousin Ferry Marisan for the first time there. He always visited me when he was in the Netherlands. He entered politics in 2019. I said, “Fer, that means your death, you’ll end up just like Arnold Ap”. Fer was also a musician, anthropologist, but also director of the human rights organization. And they just killed him in the hospital with another important Papuan man.

Bow with arrows

Year: unknown

Wisselmeren, Dutch New Guinea

Donation by Willem Prins

My brother Dammis Prins was stationed in New Guinea as a conscript in 1955/1956. He was a liaison officer in the Navy and returned to the Netherlands just before the Obano uprising in 1956, so for about a year and a half he was there. Unfortunately, he passed away in 2019 and I actually wanted to ask him a bit more. He had a lot of fun there, that much I know. He left me a bow and arrows and a number of photographs. He had taken the bow and arrows with him as a souvenir. He probably bought it at the Wisselmeren.

Via Biak he ended up in Manokwari and from there went on several patrols in the bush as a radioman. For example, small patrols of 10, 12 days where two tribes were at war and then they went there with a missionary. They took pigs with them and then they went to make peace between those two tribes.

He made few notes of his adventures. What he did do was make notes on the back of the photos. For example, the cinema on Biak, the Krasnadrumsky. Krasna is probably from Krasnapolsky, but the Drumsky because they made a movie theater out of oil drums, just in the open air. He told me those stories and also about swimming on Biak, from the bathing jetty.

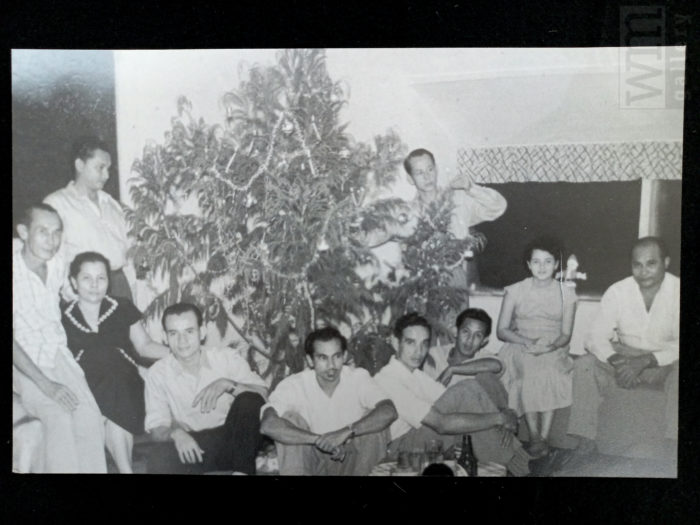

Chopping ax with Kali stone (Kali Batu). Photo around the Christmas tree in New Guinea.

Year: 1950-1960

Hollandia (Jayapura), Dutch New Guinea

Loan from Miluska Dias

Our father, Gerard Hendrik Dias, was born November 21, 1927 in Medan, Sumatra, and lived from 1950 to 1960 in Hollandia in New Guinea. He was a civil servant there and was in his early twenties, coming from a traumatic period as an Indo. Now that we ourselves (2nd generation and both 40+ – my father had us at a later age) are a bit older, we would like to know how he experienced that period. My father was silent, so I know very little. Later in life my father painted a lot and terrible paintings emerged, especially about the period in the camp.

He loved to photograph and has an entire album full of the period in New Guinea, in which daily life is reflected in particular. As a child I loved this photo album, it showed a life I didn’t know. The focus was on having fun, eating, exercising together and togetherness. But also, a life without parents / family and saying goodbye to your home. I still enjoy looking at this album. It gives me a warm feeling. Everything was celebrated very lavishly. My father loved it there, he fell in love there, he had his best friends there.

He brought spears, a hatchet, and shells to the Netherlands. They were given a prominent place in our parental home. Now that my father is gone (he passed away in 2005) they now hang in my brother’s house. Together with the photo album, these objects are a tangible reminder of our father.

Cross and signal horn

Year: unknown

Asmat, Dutch New Guinea

Loan from Maurits Beltgens

My father Gerard Beltgens was a police commissioner in Dutch New Guinea. He attended the police school in Soekaboemi on Java, then he was sent to New Guinea to Merauke and Hollandia. I’m an Indo Putih, let’s call it a white Indo.

In 1959 my father accompanied a Dutch/French film expedition. This expedition was interested in the Asmat, who had had hardly had contact with whites. My father made himself available to guide and protect the expedition because he was responsible for this area and knew the language and customs of the people well. He went on patrol in this area four to five times a year. A film of the expedition was also made. Sky Above – Mud Beneath, which won an Oscar in 1961 for best documentary.

There was also a Dutch missionary on the expedition, Father van Kessel, to bring Christianity. I also inherited something very special from my father that the Papuans had made after the mission; a double cross.

My father always said that these were the best years of his life. I was very young then and when my father went on patrol with his Papuan soldiers, he also went to those inaccessible areas. The Asmat had also given him various ethnographic artefacts as a thank you.

Decorated piece of bone with a piece of cassowary feathers and a matching bag to make a fire. Emblem of the Papua Volunteer Corps cassowary on oval red background.

Year: late 1950s

Manokwari, Dutch New Guinea

Loan by Roy Kloeth

I was born on April 7, 1945 in Jakarta. On January 1, 1950, we arrived in Hollandia from Tanjung Priok with the KPM ship Waibalong. We lived in Hollandia Binnen with Pa and Ma and my three younger brothers until May 1952. Not long after the catering business was sold, we left for the Netherlands that same year. In 1953 Pa returned to Dutch New Guinea, he had a job in Manokwari. Ma and us 4 boys arrived in 1954 at that beautifully situated spot on the Doreh Bay. A stone’s throw away are the two ‘Islands in the Sun’, Pulau Mansinam and Pulau Lemon, located in the bay. With the seaside resort of Pasir Putih, where young and old gathered, swam, and relaxed on the clean beach. Delicious under the cooling low overhanging dense foliage of the Ketapang beach tree. Home-made Lemper, Pisang Goreng or Loempia were in great demand. On August 5, 1960 I left Manokwari, I was 15 and on my way to the Netherlands. Painfully leaving a part of my childhood behind.

The piece of bone with cassowary feathers is an authentic utensil once received from a Papuan. A humble and lovable person living behind our house. We had a lot of contact with him and his children and I got this from him when we had to leave in 1960. He built fires with the artfully decorated piece of bone and flammable dried moss in the bag. Ma gave me the Papua Volunteer Corps emblem with the image of a cassowary. The hastily established PVK (Papuan Volunteer Corps) (late ‘58/’59) was stationed in a barracks outside the city of Manokwari. Emblem text Persevero (I persevere).

What I have a problem with is that in the 1970s we were so committed to the story of Nelson Mandela while we left people to fend for themselves in our own backyard.

Morgenster (Morning Star) with signatures F-Compagnie 6 IB

Year: 1962

Sorong, Dutch New Guinea

Loan by Tom Derde

The Papuan flag was the Independence flag of the people of Dutch New Guinea. For the locals – the Papuans – a symbol to be proud of and cherish. For us soldiers this flag was also a valuable symbol as a reminder of camaraderie in difficult times. That’s why there are as many signatures as possible from colleagues on this flag, to keep the connection with each other and the country visible!!

From 27 June 1962 to 7 November 1962, I was a conscript sergeant in Sorong and Jefman. It is sad and disappointing for the Papuans that the Dutch government imparted completely wrong information about independence to this ethnic group. And also, for many soldiers who had worked there, there was the feeling for a long time that, “we let the Papuans down”. This also applied to me.

Necklace

Year: unknown

Baliem Valley, Papua

Loan by Erik Macville

I am second generation; I came to the Netherlands when I was sixteen. Aboard the Willem Ruis with my parents. My sister went to Sorong when she was 24, where she became the head of the hospital’s housekeeping. She actually followed her boyfriend who was there for his military service, but she met her husband there who worked at Shell in Biak.

In 1992 I made a month-long trip through West Papua as part of a group of 10 Dutch people, led by a local anthropology student and a Papuan guide who the student still knew from his youth. We started in Biak because that’s where you landed and I visited the hospital where my sister worked, from 1960 to 1962. But I was mainly able to talk to the Papuans because in 1992 I had already followed a few Indonesian courses here in the Netherlands. I did not want to learn it in all of my 14 years in the Dutch East Indies. So I could talk to them and they weren’t suspicious either. They saw a Belanda, a white one, and they had such good experiences with the Dutch, so all I heard was that they hoped that the Dutch would come back again. I bought some items mainly in the Baliem Valley. Among other things, a necklace, a necklace made of bones.

Pen drawing of submarine hunter Hr.Ms. Friesland

Year: 1962

Misool, Dutch New Guinea

Loan by Arend Pottjegort

As a third-class cook, I was one of the crew members of the Hr.Ms. Friesland. I was the last Dutchman who was sent to a war zone as a minor, I was 17 years old. On February 14, 1962, the Friesland left for New Guinea. We felt that we had to steer the Papuans towards self-determination. On August 17, 1962, the Marines were engaged in an intensive combat mission against a large number of Indonesian infiltrators; the Battle of Misool – the last naval battle in Dutch New Guinea. Hr.Ms. Friesland gave support fire. I was the ammunition loader at the 40mm machine gun; the Oerlikon. The infiltrators were often spotted by the Papua Volunteer Corps or by the Kampong residents. Then the Marines would go in and neutralize them. A day later, on August 18, 1962, the armistice followed. We were a bit disappointed though. It was suddenly over. We were of the opinion that we could’ve handled them. I’m proud of what we all did, but I’m not proud that we completely failed New Guinea. The Papuans are a beautiful people. That’s actually who we did it for, because you knew how the Indonesians felt about the Papuans. One colonizer leaves and another dictator takes its place. The Dutch government let it slide, to put it very nicely.

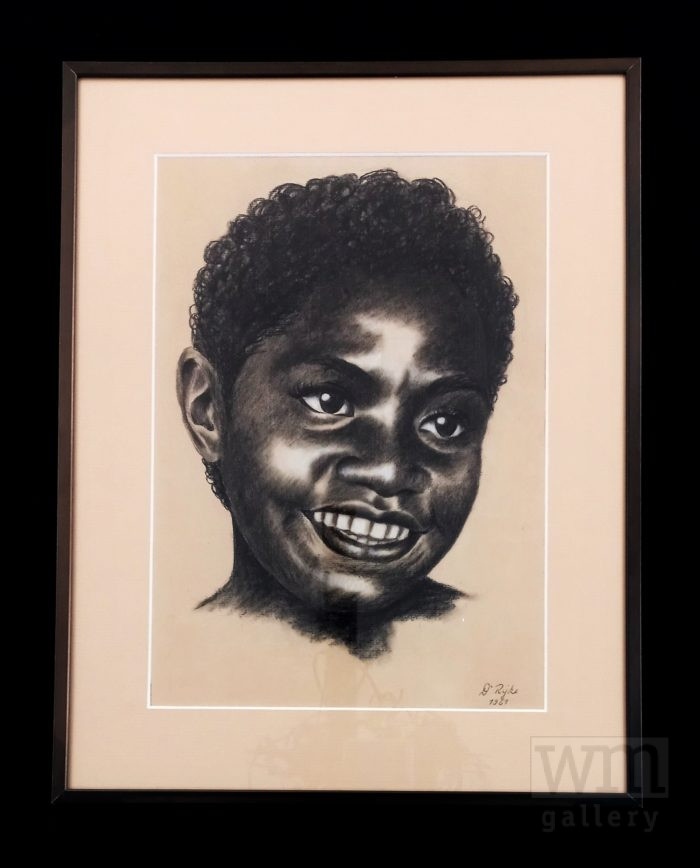

Pot with sand and pot with red soil. Painting of a Papuan girl

Year: 2017/1961

Hollandia (Jayapura), Dutch New Guinea

Loan by Veronica Wttewaall

My father came to Merauke with his family in 1946 for the reconstruction. I was born there in 1951, and after that we lived on Biak and in Hollandia. My father also worked as an agronomist at the experimental garden in Kota Nica and trained young Papuans. They tried to figure out what could grow, but nothing ever came of it. However, just before our forced departure, the first bar of chocolate came on the market, as an example. I remember well that I played at war with 2 neighboring boys (I was 10 years old). One stood for America, the other Indonesia and the last was the Netherlands. It was a kind of hide and seek.

I went back twice. My father never wanted to go back, but my mother has been back a few times. In 1974 was the first time for me, not long after we left, then it still looked very recognizable. And 5 years ago, I went back and it was quite a shock. Especially in Hollandia, Biak was still very beautiful, really great. But Hollandia is terrible, very polluted. You see very few Papuans, only in the marketplace. Everything else is in the hands of Indonesian people.

The pots of red soil and sand represent my childhood. Always playing outside, I had a great childhood there. The red earth from Hollandia. After playing you were so dirty because of the red soil that you had to take a shower for the second time that day. And the sand is from Base G beach in Holllandia. That was our outing every Sunday. The last time I took those jars with me was five years ago. The red earth and the sand. Paradise on Earth.

The Papuan portrait was bought by my parents. Opposite the building of the newly installed New Guinea Council, there was a small kiosk where Papuan ethnographic artefacts were for sale. There was more attention paid to the Papuan art. I later got the portrait from my parents.

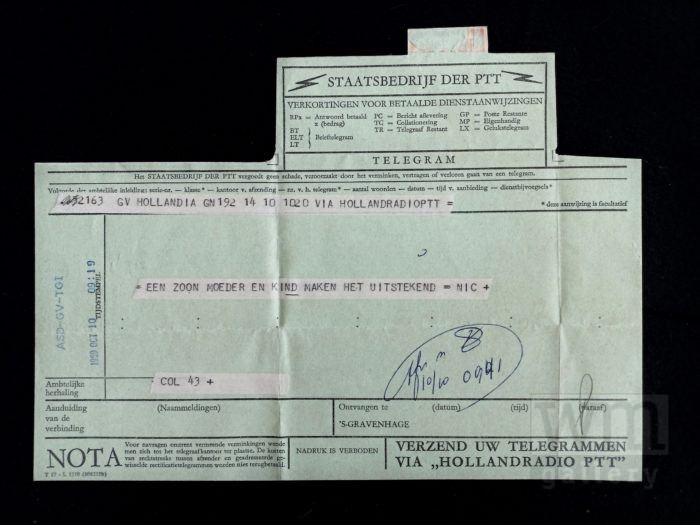

Telegram

Year: 1959

Hollandia (Jayapura), Dutch New Guinea

Document by Nico Jouwe

‘A son, mother and child are doing very well = Nic’. This sentence, typed on white telex tape, pasted onto a green piece of folded paper – better known as a telegram – announces my birth in Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea on October 10, 1959. I was born at 5:30 in the morning in what, according to my father (Nicolaas Jouwe, “Nic” for short), was the most modern hospital in the Pacific in the 1950s. He sent the telegram via Hollandradio PTT at 09:19 to his Eurasian mother-in-law, who lived at Stokroosstraat 43 in The Hague, where it was delivered the next day. Fortunately, the message had ‘already been communicated by telephone’ to the recipient on the day it was sent. A few months later I would arrive at the Stokroosstraat myself, because my mother was due for leave and she moved in with her mother for a few months, together with me and my brother. And so, in 1960 I celebrated my first birthday with my Indian grandmother in the flower district of The Hague. Not long after that birthday we flew back to Hollandia, that paradise place where the waves of the Pacific gently lapped against the posts of my father’s kampong built in the bay. Incidentally, his life mainly took place ashore, where the New Guinea Council was set up, the parliament of which he would become vice-chairman and where the Morgenster (Morning Star) flag that he designed would fly in front of the door. I played on the beach at Base-G or in the jungle and when I was thirsty, I drank coconut milk from a freshly chopped coconut. I had no knowledge of the New Guinea crisis that erupted at that time. But it eventually meant that our family had to flee Hollandia in mid-August 1962. Bewildered we sat on the plane destined for the Netherlands. As a consolation, a flight attendant gave me a bear during the flight. Once we landed, we moved back in with my grandmother in the Stokroosstraat in The Hague.

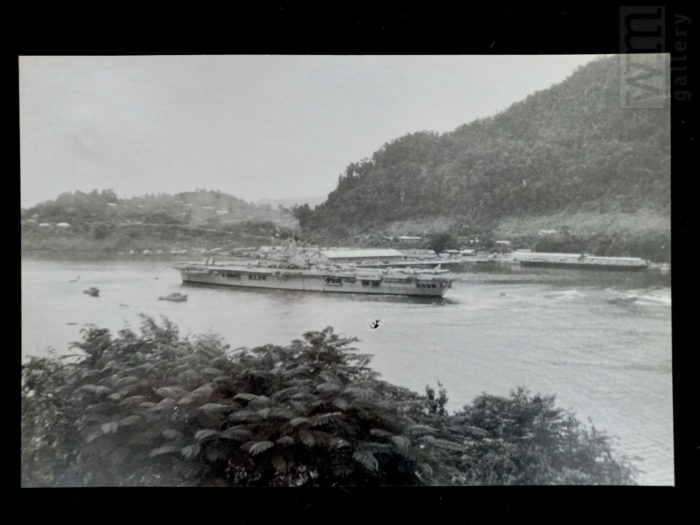

The view from the parental home of Robert Nieuwenhuijs on dok2 over the Humboldt Bay with the arrival of the only Dutch aircraft carrier, the Karel Doorman

Year: 1960

Hollandia (Jayapura), Dutch New Guinea

Photo by Robert Nieuwenhuijs

I was born in 1942 and left Albergen in 1945 for New Guinea. My father was already in New Guinea, he arrived there in 1946 for the Netherlands East Indies Civil Administration, to get the administration of government affairs in order after the Japanese capitulation. My grandfather had already been to New Guinea and my great-great-grandfather was one of the last residents in the Moluccas. In New Guinea, my father set up a number of businesses, from transportation to airlines.

In 1961 I went to the Netherlands. My father always said we were just sold out by the Americans. I found in my father’s papers a speech by Soebandrio, Indonesia’s foreign minister between 1957 and 1966, which he gave in New Guinea about the transfer. I have to say my first reaction was: “I‘m disgusted by what he said”. I think they just stole New Guinea from us. If that hadn’t happened, I would still be living there. People always talk about decolonization, but it hasn’t been that at all. It was just occupied like East Timor.

Wall decoration

Year: unknown

Hollandia/Jayapura, Papua

Loan by Gita Viset

My father worked and lived in New Guinea for 30 years, my mother married my father by proxy, they had met when my father was on leave in the Netherlands, my mother had come earlier from the Dutch East Indies. My mother then followed my father to New Guinea.

My father was taken by his father as a 10-year-old boy because my grandfather had to go on a gold hunt, which was all the rage at the time; with the gold rush to New Guinea. Somewhere in the Wisselmeren area. And he did indeed find gold, because he was with two friends and they became very rich, but my grandfather was shot. My father was there as a 10-year-old with two younger brothers, who then ended up with a foster family. He worked there and sent money to his mother in Java, who had many younger children. And then the war broke out, and he became a prisoner of war and had to work there on the construction of an airfield. But my father escaped and swam across to Australian New Guinea. My parents married by proxy and my mother followed my father to New Guinea

In 1992 I went to Hollandia/Jayapura with my parents and brother. My father had worked and lived there for a long time. And my brother was born there, the hospital was still there. After 30 years, my father was still recognized by a number of people. And they thought my father had come back to help them. On the day we left, half the village accompanied me to the airport and my father struggled to free me from the embraces of the Papuans. Jangang lupa, orang papua, don’t forget the Papuans. Tears were in their eyes. I got a lump in my throat when I saw that they had given us a farewell present. We got it wrapped in a newspaper pressed into our hands when boarding the plane. All those crying Papuans and those words, that has always stayed with me. Later I read about the genocide that had taken place there.